- Home

- Simon Beckett

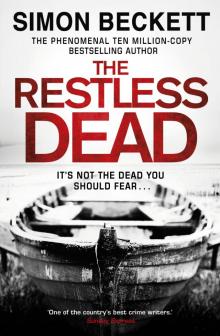

The Restless Dead

The Restless Dead Read online

About the Book

‘Composed of over sixty per cent water, a human body isn’t naturally buoyant. It will float only for as long as there is air in its lungs, before gradually sinking to the bottom. If the water is very cold or deep, it will remain there, undergoing a slow, dark dissolution that can take years. But if the water is warm enough for bacteria to feed and multiply, then it will continue to decompose. Gases will build up, increasing the body’s buoyancy. And the dead will literally rise …’

What promises to be a long bank holiday for forensics consultant Dr David Hunter is interrupted by a call from Essex police. A badly decomposed body has been found in a desolate area of tidal mudflats and saltmarsh called the Backwaters.

Under pressure to close the case, the police want Hunter to help with the recovery and identification. It’s thought the remains are those of Leo Villiers, the son of a prominent businessman, who vanished weeks ago. To complicate matters, it was rumoured that Villiers was having an affair with a local woman. And she too is missing.

Yet Hunter has his doubts about the identity, knowing the condition of the unrecognizable body could hide a multitude of sins. Then more remains are discovered – and these remote wetlands begin to give up their secrets …

With its eerie, claustrophobic sense of place, viscerally authentic detail and explosive heart-in-mouth moments, The Restless Dead offers a masterclass in crime fiction and marks the stunning return of one of the genre’s best.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Simon Beckett

Copyright

The Restless Dead

SIMON BECKETT

For Hilary

1

COMPOSED OF OVER sixty per cent water, a human body isn’t naturally buoyant. It will float only for as long as there is air in its lungs, before gradually sinking to the bottom. If the water is very cold or deep, it will remain there, undergoing a slow, dark dissolution that can take years.

But if the water is warm enough for bacteria to feed and multiply, then it will continue to decompose. Gases will build up in the intestines, increasing the body’s buoyancy until it floats again.

And the dead will literally rise.

Suspended face down, limbs trailing below, the body will drift on or just under the water’s surface. Over time, in a morbid reversal of its formation in the womb’s amniotic darkness, it will eventually come apart. The extremities first: fingers, hands and feet. Then arms and legs, and finally the head, all falling away until only the torso is left. When the last of the decompositional gases have seeped out, the torso too will slowly sink a second, and final, time.

But water can also cause another transformation to take place. As the soft tissues decompose, the layer of subcutaneous fat begins to break down, encasing a once living human body in a thick, greasy layer. Known as adipocere, or ‘grave-wax’ to give it its more colourful title, this pallid substance also goes by a less macabre name.

Soap.

Cocooned in its dirty white shroud, the internal organs are preserved as the body floats on its last, solitary journey.

Unless chance brings it once more into the light of day.

The skull was a young female’s, the gender hinted at by its more gracile structure. The frontal bone was high and smooth, lacking any bulge of eyebrow ridges, while the small bump of the mastoid process beneath the opening of the ear looked too delicate for a male. Not that such things were definitive, but taken together they left me in little doubt. The adult teeth had all broken through by the time of death, which indicated she was older than twelve, though not by much. Although two molars and an upper incisor were missing, probably dislodged post-mortem, the remaining teeth were hardly worn. It confirmed the story told by the rest of her skeleton, that she’d died before reaching her late teens.

The cause of death was all too obvious. At the back of the skull, a jagged hole about an inch long and half that wide sat almost dead centre of the occipital bone. There was no sign of healing and the edges of the wound were splintered, suggesting the bone was living when the injury occurred. That wouldn’t have been the case if the damage had been inflicted after death, when the bone dries out and becomes brittle. The first time I’d picked up the skull I’d been surprised to hear an almost musical rattle from inside. At first I’d thought it must be bone fragments, forced into the brain cavity by whatever object had killed the young victim. But it sounded too large and solid for that. The X-ray confirmed what I’d guessed: loose inside the girl’s skull was a slender, symmetrical shape.

An arrowhead.

It was impossible to say exactly how old the skull was, or how long it had lain in the ground on the windswept Northumberland moors. All that could be said with any certainty was that she’d been dead over five hundred years, long enough for the arrow shaft to disintegrate and the bone to darken to a caramel colour. Nothing would ever be known about her; not who she was nor why she’d died. I liked to think whoever had killed her – as she was either turned or running away – had received some sort of punishment for the crime. But there was no way of knowing that either.

The arrowhead shifted with a soft percussive noise as I packed away the skull, carefully wrapping it in tissue paper before replacing it in its box. Like the other historical skeletons in the university’s anthropology department, it was used to train undergraduates, a morbid curio sufficiently ancient as to be largely devoid of shock. I was used to it – God knows, I’d seen worse – but that particular memento mori always struck me as particularly poignant. Perhaps it was because of the victim’s youth, or the brutal manner of her death. Whoever she was, she’d once been someone’s daughter. Now, centuries later, all that remained of the nameless girl was stored in a cardboard box in a lab.

I put the box back in the steel cupboard with the rest. Rubbing a stiffness from my neck, I went into my office and logged on to my computer. There was the familiar Pavlovian expectation as the emails loaded. As usual, it was replaced by disappointment. There was only the everyday minutiae of academic life: queries from students, memos from colleagues and the occasional appeal the spam filter had failed to catch. Nothing else.

It had been like that for months.

One of the emails was from Professor Harris, the new head of anthropology, reminding me to schedule a meeting with his secretary. To review options regarding your position, as he delicately phrased it. My heart sank when I read that, but it was hardly a surprise. And it was a problem for the following week anyway. Turning off the computer, I hung up my lab coat and pulled on my jacket. A postgraduate student passed me in the corridor as I left.

‘’Night, Dr Hunter. Have a good holiday,’ she said.

‘Thanks, Jamila, you too.’

The thought of the long bank holiday weekend lowered my spirits even further. I’d foolishly accepted an invitation to spend it with friends at their house in the Cotswolds. That had been weeks ago, when it had seemed distant enough not to worry about. Now it was here I was less sanguine, not least since there would be a lot of other guests there I didn’t know.

Too late now. I unlocked my car, swiping my pass against the scanner and waiting for the barrier to rise. I knew it was stupid driving in to the university each day, contending with London traffic and congestion charges rather than catching the Tube, but the habit was hard to break. As a police consultant I’d grown used to being called out to different parts of the country when a body was found, often at short notice. It had made sense to be able to leave quickly, but that was before I’d been unofficially blacklisted. Now taking my car in to work was beginning to seem less like a necessary routine and more like wishful thinking.

On the way home I stopped off at a supermarket to buy the sorts of things I remembered a house guest ought to take. I wasn’t setting off until morning, so I needed something for dinner that evening as well, and wandered the shelves without any great enthusiasm. I’d been feeling vaguely under the weather for a few days now, but put it down to boredom and apathy. When I realized I was browsing the ready meals section I gave myself a mental slap and moved on.

Spring was late arriving this year, the winter winds and rain lingering well into April. The overcast skies did little to lengthen the days, and it was already growing dark by the time I pulled on to the road where I lived. I found a parking space and carried the shopping bags back to my flat. It occupied the ground floor of a large Victorian house, with a small entrance hall shared with another flat upstairs. As I drew nearer I saw there was a man in overalls working on the front door.

‘Evening, chief,’ he greeted me cheerily. He was holding a plane, assorted tools spilling out of the open bag at his feet.

‘What’s going on?’ I asked, taking in the raw timber around the lock and wood shavings littering the floor.

‘You live here? Someone tried to break in. Your neighbour called us out to repair it.’ He blew sawdust off the door edge and set the plane back on it again. ‘You don’t want to be leaving the place unlocked in this neighbourhood.’

I stepped over his toolbag and went to speak to my neighbour. She’d only been living in the upstairs flat for a few weeks, a flamboyantly attractive Russian who, as far as I could tell, worked as a travel agent. We’d rarely spoken beyond the odd pleasantry, and she didn’t invite me over the doorstep now.

‘It was broken when I came home,’ she said. A wave of musky perfume radiated from her as she tossed her head angrily. ‘Probably some junkie, trying to get in. They steal anything.’

The neighbourhood wasn’t exactly high-rent, but it didn’t have any more of a drug problem than anywhere else. ‘Was the front door open?’

I’d checked my own flat but its door was intact. There was no sign that anyone had tried to force their way in. My neighbour shook her head, setting the thick, dark hair bouncing. ‘No, only broken. The scumbag got frightened or gave up.’

‘Did you call the police?’

‘Police?’ She gave a phhf of disdain. ‘Yes, but they don’t care. They take fingerprints, they shrug, they go. Better to get a new lock. A strong one this time.’

It was said pointedly, as though the old lock’s failings were my fault. The locksmith was finishing up when I went back downstairs.

‘All done, chief. It’ll need a new lick of paint, stop the planed wood from swelling when it rains.’ He raised his eyebrows, holding up two sets of keys. ‘So, who wants the bill?’

I looked back upstairs at my neighbour’s door. It remained closed. I sighed. ‘Do you take cheques?’

After the locksmith had gone, I fetched a pan and brush to sweep up the sawdust in the hallway. A curl of shaved wood had wedged itself in the corner. I crouched down to brush it up, and as I saw my hand against the black and white tiles I had a dizzying rush of déjà vu. Lying in the hallway, a knife sticking obscenely from my stomach, blood spreading across the chequerboard floor …

It was so vivid it took my breath. I stood up, heart racing as I forced myself to breathe deeply. But the moment was already passing. I opened the front door, drawing in the cool night air. Christ. Where did that come from? It was a long time since I’d had a flashback to the attack, and this one had come out of nowhere. I rarely even thought about it any more. I’d done my best to put it behind me, and while the physical scars remained, I’d thought the psychological wounds had healed.

Obviously not.

Recovering, I emptied the sawdust into the bin and went back into my flat. The familiar space was just as I’d left it that morning: inoffensive furniture in a decent-sized lounge, with a kitchen and a small, private garden out back. It was a perfectly good place to live, but now, with the flashback still fresh in my mind, I realized how few of the memories I had of this place were happy ones. Like taking my car to work, the only thing that had kept me here was habit.

Perhaps it was time for a change.

Feeling listless, I unpacked my shopping and then took a beer from the fridge. The fact was I was in a rut. And change was coming whether I wanted it or not. Although I was employed by the university, most of my work came from police consultancy. As a forensic anthropologist, I was called in when human remains were found that were too badly decomposed or degraded for a pathologist to deal with. It was a highly specialized field populated largely by freelancers like myself, who would help police identify remains and provide as much information as possible regarding the time and manner of their dying. I’d become intimate with death in all its gory excess, fluent in the languages of bone, putrefaction and decay. By most people’s standards it was a gruesome occupation, and there were times when I struggled with it myself. Years before, I’d lost my wife and daughter in a car accident, their lives snuffed out in an instant by a drunk driver who’d walked away unscathed. Haunted by what had happened to them, I’d abandoned my work and returned to my original career as a GP, tending to the concerns of the living rather than the dead. I’d buried myself away in a small Norfolk village, trying to escape any connection to my old life and the memories that came with it.

But the attempt had been short-lived. The realities of death and its consequences had found me anyway, and I’d come close to losing someone else I loved before accepting that I couldn’t run away from who I was. For better or worse, this was what I did. What I was good at.

Or at least it had been. The previous autumn I’d become involved with a brutal investigation on Dartmoor. By the end of it two of the police’s own were dead and a senior ranking officer had been forced to resign. While I wasn’t to blame, I’d been an unwitting catalyst for the scandal that ensued, and no one likes a troublemaker. Least of all the police.

And suddenly the consultancy work had dried up.

Inevitably, there was a knock-on effect at the university. Technically, I was only an associate, on a rolling contract rather than tenure. The arrangement gave me the freedom to carry on with my police consultancy and allowed the department to benefit by association. But an associate who worked on high-profile murder investigations was a far cry from one who’d suddenly become persona non grata with every police force in the country. My contract only had a few more weeks to run, and the new head of anthropology had indicated that the department wouldn’t carry any dead weight.

It was clear that was how he saw me.

With a sigh I flopped back into an armchair and took a drink of beer. The last thing I felt like was a weekend house party, but Jason and Anja were old friends. I’d known Jason since medical school, and met my wife at one of their parties. Along with everything else, I’d let the friendship slide when I left London after Kara and Alice died, and never quite got around to re-establishing it when I moved back.

But Jason had got in touch just before Christmas, after see

ing my name in news reports about the fouled-up Dartmoor investigation. I’d met up with them several times since, and been relieved there’d been none of the awkwardness I’d expected. They’d moved home since we’d lost touch, so at least I was spared the bittersweet memories their old house would have brought. They now lived in an eye-wateringly expensive house in Belsize Park, and had a second home in the Cotswolds.

That was where I’d be driving to tomorrow. It was only after I accepted the invitation that I learned there was a catch.

‘We’re inviting a few other people,’ Jason told me. ‘And there’s someone Anja would like you to meet. She’s a criminal lawyer, so you should have plenty in common. Police stuff and all that. Plus she’s single. Well, divorced, but same thing.’

‘That’s what this is about? You’re trying to set me up with someone?’

‘I’m not, Anja is,’ he explained with exaggerated patience. ‘Come on, it’s not going to kill you to meet an attractive woman, is it? If you hit it off, great. And if not what’s the harm? Just come along and see what happens.’

In the end I’d agreed. I knew he and Anja meant well, and it wasn’t as though my social calendar was exactly full these days. Now, though, the prospect of spending a bank holiday weekend with strangers seemed like a terrible idea. Can’t cry off now. Better make the best of it.

Wearily, I got up and began making myself something to eat. When the phone rang I thought it would be Jason, calling to check I was still going. The possibility of making a last-minute excuse crossed my mind, until I saw the number on the caller display was withheld. I almost didn’t answer, thinking it must be a marketing call. Then old habits kicked in again, and I picked up anyway.

‘Is that Dr Hunter?’

The speaker was male, and sounded too old for a telemarketing call. ‘Yes, who’s this?’

‘I’m DI Bob Lundy, Essex Police.’ The voice was unrushed, almost slow, its accent northern rather than estuary. Lancashire, I thought. ‘Have I caught you at a bad time?’

Where There's Smoke

Where There's Smoke The Chemistry of Death

The Chemistry of Death Written in Bone

Written in Bone Stone Bruises

Stone Bruises The Calling of the Grave

The Calling of the Grave Whispers of the Dead

Whispers of the Dead The Restless Dead

The Restless Dead Owning Jacob

Owning Jacob Fine Lines

Fine Lines Whispers of the Dead dh-3

Whispers of the Dead dh-3 Owning Jacob (1998)

Owning Jacob (1998) Where There's Smoke (1997)

Where There's Smoke (1997) Written in Bone dh-2

Written in Bone dh-2 The Chemistry of Death dh-1

The Chemistry of Death dh-1 The Calling Of The Grave dh-4

The Calling Of The Grave dh-4